Situated in different parts of the world, the Rotary Peace Centers offer tailor-made curricula to train individuals devoted to peacebuilding and conflict resolution — no matter where they land

Rita Lopidia vividly recalls her experiences as a Rotary Peace Fellow at the University of Bradford in England. “The classes in African politics and UN peacekeeping were my favorite,” she says. “The politics course challenged me to dig deeper into research to understand the history of the continent, and the peacekeeping class aided my understanding of global politics. As a practitioner, that was an eye-opener to have a global view of events happening around the world.”

Lopidia’s time at the Rotary Peace Center profoundly affected her. “After graduation, I traveled back to Africa and settled in Uganda due to the ongoing conflict in South Sudan,” she explains.

“There I established the EVE Organization for Women Development and started engaging the South Sudanese refugees in Uganda and their host communities. Through my organization, we were able to mobilize South Sudanese women to participate in the South Sudan peace process promoted by eastern Africa’s Intergovernmental Authority for Development — and that led to the signing of the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan in 2018.”

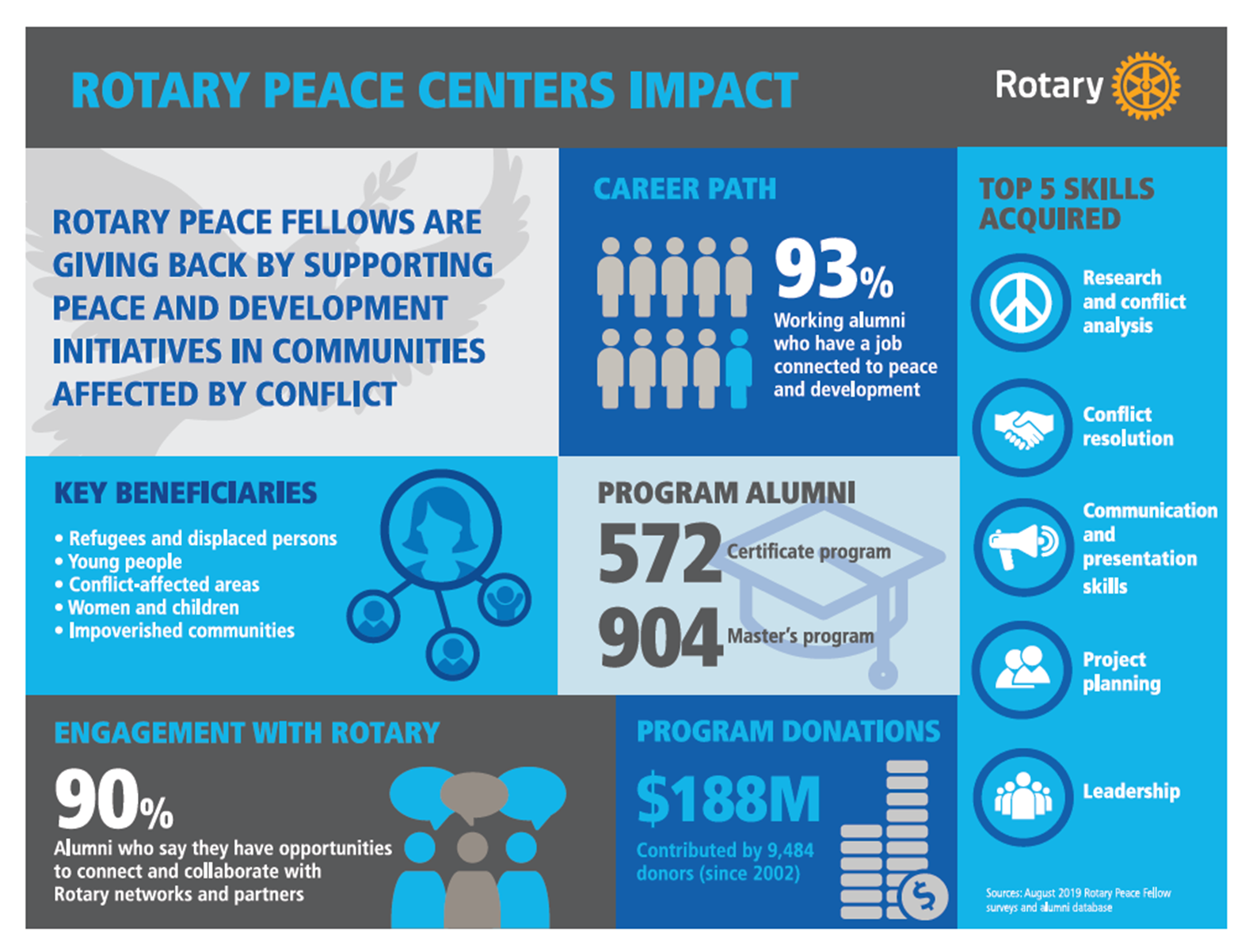

Lopidia is just one of the 1,500- plus peace fellows from more than 115 countries who have graduated from a Rotary Peace Center since the program was created in 1999; the first peace centers began classes three years later. Currently, Rotary has seven peace centers in various locations around the world; the newest, at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda — the first in Africa — welcomed its inaugural cohort of peace fellows in 2021. Next, Rotary plans to establish a peace center in the Middle East or North Africa, perhaps as soon as 2024, and has set its sights on opening one in Latin America by 2030.

As you will discover, the curriculum at each peace center has been carefully crafted to address specific aspects of the peacebuilding process — and train the next generation of global change-makers. To learn more about the Rotary Peace Centers and how to nominate a peace fellow or apply for a fellowship, go to rotary.org/peace-fellowships.

Chulalongkorn University – Bangkok

When a coup took place in Myanmar in February 2021, the peace and development studies program at Chulalongkorn University worked to recruit and support peacemakers there. Six months later, during the evacuations in Afghanistan that followed the resumption of Taliban control, the program created an entire network to get people, including more than one Chula alumnus, out of the country. “We are looking for fellows who are sitting on the front lines of conflict,” says Martine Miller, deputy director of the Rotary Peace Center at the university. Those can include a peace fellow who works with young people in prison systems in California or one focusing on at-risk youth in Kenya.

The nontraditional lecturers of the interdisciplinary one-year program have been embedded in conflict areas themselves. They include Gary Mason, a Methodist minister who has been involved in Northern Ireland’s peace process, and Jerry White, co-founder of Landmine Survivors Network, who lost part of a leg to a land mine in Israel. “It’s not the typical classroom,” says Miller. “The instructors are not professors. They’re writing articles and books. They’re out there in the field doing it. And they’re certainly not bashful.”

Since the peace center was established 17 years ago, the curriculum has evolved to include discussions of gender identity and a session on psychological well-being and trauma meant to tackle head-on the inherent stress of the conflict resolution field. Chula’s long history of innovation has paid off: Seventy-five percent of the more than 500 alumni work for United Nations and government agencies, for nongovernmental organizations, or in academia and research.

University of Bradford – Bradford, England

Home to the largest program in the world devoted to peace studies, conflict resolution, and development, this diverse public research university in northern England offers seven different master’s degrees in peace and conflict studies and has educated students from more than 50 countries. The sheer breadth of the program means Rotary Peace Fellows can focus on anything from sustainable development to contemporary security issues. “We don’t simply look at conceptual issues,” says Behrooz Morvaridi, the peace center director. “The program prepares the students to go and implement what they learn at the practical level.”

During their 15 months at Bradford, peace fellows can participate in field studies in Africa, Northern Ireland, and other locations, where they talk to political leaders and immerse themselves in the regions’ institutions and issues. The trips become real-life opportunities to see how contemporary trends involving the environment, social division, climate change, and resource scarcity can affect peace — and the ways in which communities show resilience in the face of conflict. Then there’s the trip to Oslo, Norway, to visit the Nobel Peace Center and some of the world’s preeminent peacebuilding institutions or to The Hague to learn about the International Criminal Court system in action.

The fellowship’s most popular activity, though, is the “Crisis Game,” an off-site simulated conflict management scenario of an international situation in which each student plays a role, such as ambassador, journalist, or world leader. “Students come up with great ideas to solve the problems, but [students representing] other countries come with ideas that disrupt them,” says Morvaridi. “They learn specifically what the challenges are, how politics play a role, and how difficult problems are to solve.”

University of Queensland – Brisbane, Australia

As one of Australia’s largest universities, UQ has long been known as a research innovator in the social sciences, a strength reflected in the 18-month Master of Peace and Conflict Studies curriculum, which, for peace fellows, includes seminars on topics such as “embracing emotions.”

Members of the school’s renowned political science department focus on the role of images and emotions in shaping global politics, examining, for example, the worldwide concern for Syria’s refugee crisis prompted by the heart-rending 2015 photo of a Syrian toddler washed up on the Mediterranean shore. “We all know those iconic images, and we are emotional beings,” says Morgan Brigg, director of the peace center. “We can’t just try to suppress that. So we embrace it.”

A course in gender, peace, and security also challenges students to deconstruct “masculine” and “feminine” roles in peacemaking that traditionally equate violence with men and victimhood with women. And the program’s administrators have put various systems in place to smooth each fellow’s transition from their home country to life in Australia, such as a buddy system, where first-year fellows are matched with other fellows in their final semester.

The thoughtful approach to Queensland’s curriculum draws a wide range of fellows — everyone from a documentary filmmaker to a former U.S. Marine — who explore and contribute to the world from a range of innovative angles, including through dance, cultural tourism, sexual education, and the prevention of online crimes. “The range of ways that fellows engage with peace and conflict is really quite diverse,” says Brigg. “We want them to have the potential to be excellent professionals and innovators.”

Uppsala University – Uppsala, Sweden

The peace center at Uppsala University is known for its conflict data program, a comprehensive database of organized violence and mortality. Around the world, policymakers and practitioners from the European Union to the United Nations look to the Uppsala program as the global standard for evidence-based records — and the peace center’s fellows draw upon the same scientific approach toward social issues. “There’s a deep expertise here,” says Kristine Eck, the director. “Our fellows want to understand cause and effect, and that’s a skill set we train them in.”

Highlights of the 20-month program include a joint trip with Bradford fellows to Oslo to visit the Nobel Peace Center; there are also extended opportunities for fellows to continue self-designed field work and research. For example, in Zambia they might focus on water and sanitation, or in Korea they could learn about nuclear nonproliferation (designed to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology while promoting nuclear disarmament and the peaceful use of nuclear energy). One student assisted in a quantitative research project that explored the relationship between a society’s level of gender equality and its military effectiveness.

Sweden is proud of its history of pacifism, which enables fellows to take advantage of local events such as “Philosophy Teas,” a series of discussions about peace practitioners and philosophers led by Uppsala professor Peter Wallensteen at a century-old theater — a tradition that began as a celebration of Sweden’s 200 consecutive years of peace. “There’s an increased interest among our fellows in the skill set of peacebuilding,” says Eck. “A lot more people used to come to us wanting to learn about conflict.”

Duke University and University of North Carolina – Durham and Chapel Hill, North Carolina

The Duke/UNC fellowship program is an anomaly among Rotary Peace Centers. For starters, the 21-month curriculum offers core courses in peacebuilding and brings together fellows from two college campuses 10 miles apart, which doubles students’ resources and flexibility. It’s also the only master’s program that doesn’t offer a degree in peace studies, instead focusing on international development policy at Duke and, depending on a student’s interest, various academic specialties at UNC.

The holistic approach gives peace fellows the tools to enter pertinent development sectors such as public health and education, where they can prevent conflicts and promote peacebuilding through, say, improving sustainable development and human security. The program’s willingness to think outside the box leads to unusual instruction, with courses in water and sanitation and a peace- and development-related film series.

The classes offered are chosen for their direct utility in the field: Because monitoring and evaluation have become key job skills in the peacebuilding and humanitarian sectors, Duke/UNC offers a class in the evaluation of peacebuilding programs. “At the end of the day, employers don’t care if you understand all the theories about diplomacy,” says Susan Carroll, the center’s managing director. “They want to know that you can incorporate it into projects you work on and manage projects and budgets.”

International Christian University – Tokyo

Founded in the wake of World War II, ICU embraces the mission of the United Nations and has a strong focus on the promise of international diplomacy. Osamu Arakaki, the program’s director, was a legal officer of a UN humanitarian agency in Canberra, Australia, and associate director Herman Salton worked at the UN Headquarters in New York. The school’s emphasis on intergovernmental peacekeeping organizations is underscored in classes such as “The United Nations and Sustainable Development” and “Multilateral Diplomacy.”

“ICU holds a mission to foster international citizens contributing to the establishment of lasting peace,” says Arakaki. “And it has formed countless UN and international organization staff members and diplomats.”

The ICU Graduate School of Arts and Sciences is known for its interdisciplinary program and liberal arts approach. Fellows pursue a master’s degree in peace studies within the public policy and social research program.

The 22-month peace studies program prides itself on the open dialogue between students and instructors. Classes at the graduate level are offered in English, and the student-to-faculty ratio of 18-to-1 enables ICU to realize its mission of small-group education. A field trip to Hiroshima enables students, including some who have come from war-torn countries, to hear the voices of survivors of the nuclear bomb and witness firsthand how Japan attempts to overcome genocide through reconciliation. “The horror of Hiroshima is not simply in the past,” Arakaki says. “It is a real fear that the tragedy may be repeated in parts or even the whole of the globe in the future unless we make a concerted effort to avoid that situation.”

Makerere University – Kampala, Uganda

The newest peace center, and the first in Africa, Makerere is located in the continent’s Great Lakes region, an area with a long history of conflict. This gives fellows, a large percentage of whom are from or live in Africa, a chance to interact in the direct aftermath of conflicts — or as clashes unfold in real time. But rather than pinpointing the causes of war, Makerere’s curriculum teaches fellows to expand their notion of “peace” beyond a simple absence of violence and into measures of personal safety and growth.

One of the highlights of the yearlong program is an intense weeklong trip to Rwanda, where fellows see how media and ethnicity directly fed into the country’s mass atrocities in 1994. To learn how spirituality influences behavior in war situations, students also visit Kibeho, a small Rwandan village where Catholic schoolgirls said they experienced apparitions of the Virgin Mary that foretold the bloodshed. “Our fellows either interface with the people who have experienced the strife, or they are able to interact with the actual situations through our field excursions,” says Helen Nambalirwa Nkabala, the peace center’s director.

Makerere’s curriculum, which emphasizes human rights and refugee and migration issues, encourages students to use what Nambalirwa Nkabala calls the “no-method” approach to peacebuilding — a fluid approach that, with its emphasis on indigenous participation, allows communities to engage with the peace fellows’ social change initiatives rather then merely accepting predetermined solutions.

Learn more about the Rotary Peace Center in Kampala and meet six peace fellows who are members of the center’s first cohort, at rotary.org/africas-agents-change.